|

Operation Wayne Grey, March 1969 The Battle for Hill 947: Company D, 3/8th Hangs Tough Against the Vaunted 66th NVA Regiment

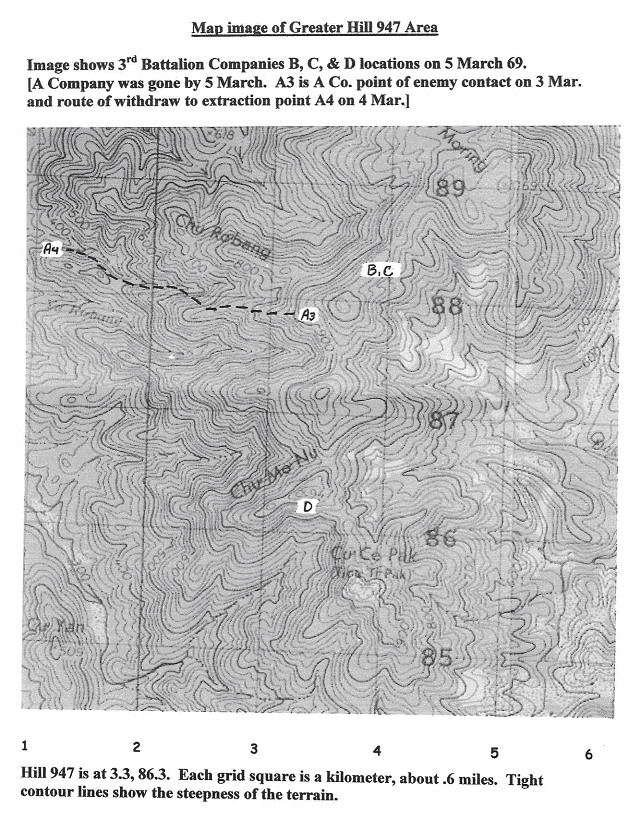

The following account is an overview of the actions of Delta Company, 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry, from 2-6 March 1969 during the Vietnam War. It is written to provide answers to questions for the survivors and as a legacy for the families and friends of those who served on Hill 947. Much of the information for this report was sorted out in a meeting among three key players of the engagement: company commander CPT Mike Daugherty, artillery forward observer 1LT Hank Castillon, and 4th platoon leader 1LT John Bauer (the author). After Action Reports and Battalion Logs were used to provide time line details. Soldiers who participated are encouraged to use this accounting as a building block upon which to add their own perspectives.

Prologue

It was early March 1969. One of the battalion’s companies, Alpha, had just been badly clawed by a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) unit and ceased to exist as a fighting unit. While remnants of beleaguered Alpha were scrambling aboard extraction helicopters, however, Delta Company decided to take the high ground and hold it. They knew they were next in line for demolition, dug in, and waited their turn. The Enemy A favorite fighting unit of both NVA commanding general Vo Nguyen Giap and North Vietnam’s President Ho Chi Minh was the 66th NVA, better known as the Tiger Regiment. Counted among its warriors were an ethnic group called Nungs, which had its roots in China and had settled in Vietnam hundreds of years earlier. It was not known if Ho Chi Minh was descended from the Nungs, but he considered this regiment his “honor” unit. In fact, the collared shirt that Ho Chi Minh wore in photographs was of Nung origin. The Nungs were bigger and stronger than their counterparts and took pride in their reputation as fighters. Also, it was the death of some Nungs in the Battle for Hill 947 that led to the belief among some that the Chinese had entered the war on behalf of N. Vietnam, though such was not the case. At any rate, their inclusion made the 66th a tough outfit. The

66th NVA operated in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. In

April of 1969, US intelligence sources knew this unit was menacing

the strategic Kontum region and was more than likely to stage new

round of operations on the anniversary of the 1968 Tet Offensive. A

North Vietnamese Army regiment would typically be comprised of 2-3

battalions and number some 1,500 men. The Battalion Mission

The assignment for neutralizing the 66th fell to the Army’s II Corps and its largest unit, the 4th Infantry Division. The 1st Infantry Brigade would be the principal player. One of the key elements in the 1st Brigade was the 3rd Battalion of the 8th Infantry, which was comprised of four companies, Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, and Delta. They were first to be inserted into the area of operation with a simple reconnaissance mission: locate the enemy. The staging area for the operation was the extensive helicopter pad at the Special Forces camp called Polei Kleng, a few miles west of Kontum City, roughly in the middle of South Vietnam, close to both Cambodia and Laos and very near the enemy supply line know as the Ho Chi Minh trail. It was considered such a hot zone that intelligence gathered by Special Forces in the area led them to advise against going in at all, at least not in company-sized units. As soon as the helicopters arrived, the companies scrambled aboard and were lifted skyward to their individual destinations in the densely forested region of the highlands, home to their enemy. The date was 2 March 1969. The month-long mission of the brigade would later be known as Operation Wayne Grey. Companies A (Alpha), B (Bravo), and D (Delta) all made some enemy contact on 3 March, but it was Alpha that early on ran headlong into the headquarters of the 66th. The NVA reacted quickly and, like ants against a hapless insect that blunders into their nest, surrounded the company, beat it badly, and sent it into a hasty withdraw. Although it put up a brave fight, the small company was no match for the larger unit. Its forty or so remaining men, of a company of about 100, were extracted from the area of operations the following day under extreme duress. The defeat of Alpha was so sudden that other units could not be deployed to their relief soon enough. Bravo Company tried to assault in by helicopter but repeatedly found the landing zones too hot, while Delta, on foot, was simply too far away. While Alpha’s initial battle raged, Delta commanding officer (CO), CPT Mike Daugherty and artillery forward observer (FO) 1LT Hank Castillon, were monitoring the radio exchange between Alpha and battalion HQ and new that Alpha was in serious trouble. They heard the crackle of gunfire amid panicky voices as Alpha was being overrun and its commanding officer killed. Because Alpha had to withdraw in haste and leave some dead and wounded behind, Delta’s orders were changed from doing reconnaissance missions to finding Alpha’s location and search for survivors. The Delta Company Mission With its new mission of finding Alpha Company men, dead or alive, and to move quickly to the site, Delta conducted an unusual night march on 3 March. It was always considered a last resort to move an infantry company at night through enemy territory in a heavily forested area. In the process, they overshot their mark on the map and found themselves in a canyon area rather than on a desired ridgeline. It was an uncharacteristic location error that actually may have saved them. Although at the time they cursed having to hump up a steep slope the next morning to get back on their original ridgeline and to their target, Hill 947. “God was on our side,” Daugherty would say later. “What we learned after the operation was over was that elements of the NVA were on the portion of the ridgeline that we went around by getting disoriented in the darkness.” 1LT Castillion was extremely concerned at this point since the company had gotten out of range of supporting artillery. Daugherty’s standard policy during any combat movement never to be out of range of supporting guns, and Castillon saw to it. When Delta reached 947, it was back in range. But it was also at the back door of the 66th, a mere 2-3 kilometers from Alpha’s battle site. Luckily, Delta arrived unnoticed. But not for long. The 4th Platoon had taken point during the day march to Hill 947 and was thus in the best readiness position to move toward Alpha’s location. It was late afternoon, about 1600, and by this time a normal operation would have called for a unit to dig in and secure a night location. But Alpha’s location was less than two kilometers away, so the decision was made to continue the mission and make a run for the site. The 1st Platoon, having joined the company late after a separate mission, would stay and secure the hill. So the 4th Platoon led the way. Sgt. Jerry Johnson was the point man. He was followed by the platoon leader, ILT John Bauer.

The Alpha POW Rescue Incident The company, with 4th Platoon out front, sped quickly but cautiously down a wide, high-speed trail. Moving with caution along a trail in enemy territory was nothing new, but what made this different was evidence of enemy activity. Communication (commo) wire straddled the side of the trail. And the sod was hard-packed, evidence of heavy traffic. Coupled with the elephant tracks seen the day before while coming up the ridgeline, there was no question that Delta was close to enemy contact, really close. A very large force was using a trail this size. Another reason for caution was that the word came down that Alpha Company, while trying to defend itself, had been seriously hurt by snipers. So the point man, Johnson, paid close attention to the trees as he pressed forward. In single file, the company moved with purpose into territory owned and operated by the 66th NVA Tigers. It should be noted that the job of pulling point was generally rotated from platoon to platoon for obvious reasons, but the 4th Platoon was geared up to take the lead despite having taken point earlier in the quest to 947. During infantry operations in Nam, the saying went that “The point man’s a dead man.” But fortune was with the platoon, and the point man to get killed belonged to the enemy. Johnson and LT Bauer, close behind, completely surprised an NVA element coming up the trail toward them. The gooks (as the enemy were called) were talking and moving casually, clearly not expecting to meet American soldiers on the trail. This fact attested to Delta’s luck at arriving undetected. As the gooks rounded a bend, Johnson and Bauer had time to get crouched in firing positions, and then they opened up. The enemy point man fell straight away. The rest flew like crazy toward the trees after returning some misdirected fire. It was an adrenalin rush, but not much of a firefight. We hit several of them. The official body count was four KIAs. During the firefight, Bauer moved behind a tree and was about to squeeze off more shots at a figure he could not miss. The figure was fewer than 15 meters away, concealed somewhat in the undergrowth. Bauer had him dead in his sights, but held off long enough to notice that the figure in the brush was no NVA. The person waved back and forth in a “Don’t shoot!” manner. He was Caucasian and yelling in clear, if frantic, English tones. There was no question of the next move, for it came from a hundred familiar movie scenes: “Get over here, I’ll cover you!” Bauer shouted, waving his arm. Bauer sprayed the area around him as other members of the company began to move forward and take charge. The newly liberated soldier was PVT Guffy (first name lost to memory), a survivor of Alpha Company. He was beside himself with joy to see friendly faces again. By this time, CPT Daugherty and 1LT Castillon, had joined Bauer, among others, and they asked him about his situation. The white orbs of Duffy’s’s flashing eyes contrasted with the filth of his face as he began his tale. It was an unforgettable moment for those around the tree as Duffy spoke. It was quite a tale, and it contrasted greatly with his joyful state of mind. At that moment, Guffy felt pretty sure that he was the only survivor. As Daugherty, Castillon, and Bauer recall, much of the conversation went like this: “They were all over us,” he began. “They were in the trees shooting down. We didn’t stand a chance, like we landed right on top of a hornets’ nest. Everyone was getting killed. I remember someone saying it was every man for himself. We tried to pull out of there.” This part of Guffy’s account was unforgettable: “I got knocked out by some concussion grenade, I guess. They must have thought I was dead. When I came to, they had me get up. Then they had me walk around with them. They shot the wounded guys. I had to watch this. I don’t know why they didn’t kill me. Maybe they needed a prisoner.” He was petty definite about the advice he gave us. “Don’t go down that trail. They’re dug in. They’ve got bunkers. They’ll be waiting. I saw lots of officers. This is a big outfit.” In reflection, it was great providence to have run into Guffy and his NVA captors. Lives were spared.

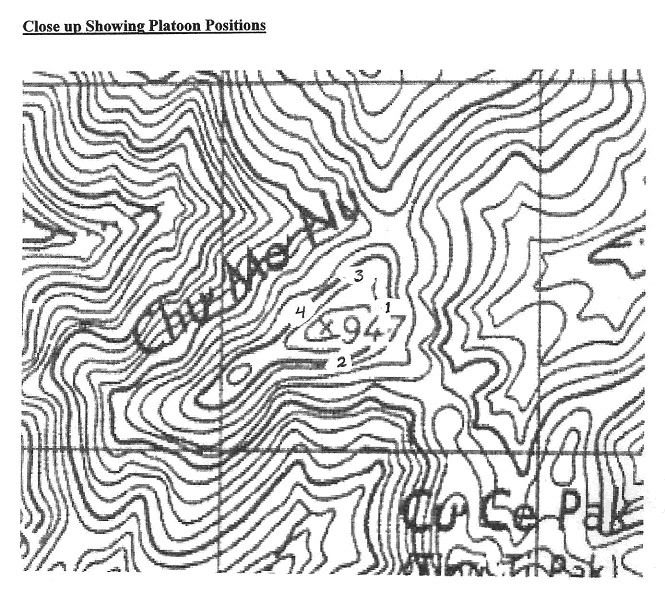

4 March 1969 Dust-off of PFC Guffy, Alpha Company survivor and ex-POW. (Photo by John Bauer) The Decision to Return Immediately to Hill 947 The question for CO Daugherty was whether or not to pursue the standing orders to search for Alpha survivors or to backtrack to Hill 947, dig in, and set up a defensive perimeter. The firefight had assured us that our presence was known to the NVA. Of that there was no question. And it looked to us, based upon the former POW’s testimony, that there were no survivors at Alpha’s old location. Plus, the 66th NVA was dug in along the trail. Daugherty weighed the options, chose not to proceed and radioed battalion about the new situation. The battalion commander, LTC Hickey, concurred. The company would dig in on Hill 947. A dust-off was ordered for PFC Guffy, and for lack of a landing zone in the dense forest, he was lifted through the trees in a basket. The Hill. In Vietnam, hills were named for their altitudes. Delta’s hill was 947 meters in elevation. Many of the trees on the hill had been downed by a 500-pound bomb, and the logs strewn about would served as cover. It was into the relative safety of the bomb’s crater that the wounded would later be placed. Three ridgelines, or fingers, fed the hill. One of them, to the north, boasted the high-speed trail that would have led to Alpha’s former position. Having had the firefight on it already, it was easily the most likely enemy attack route. This was on the mind of artillery FO Castillon, who was already at work prefiguring firing coordinates. A second high-speed avenue of approach was to the southwest. This had been our own approach route, and it was determined the least likely to be a path of enemy assault. A third finger came from the southeast. It was an unknown factor. As night fell on 4 March 1969, Delta had established its defensive perimeter on Hill 947. Recalling the earlier firefight and the words of warning from former POW Guffy, LT Bauer remembered turning to his platoon sergeant, Bruce Thompson, and remarking, “You know, pretty soon we’re going to be surrounded.” Thompson replied, “We’re probably already surrounded.” Delta knew it was camped at the rear end of the headquarters element and that the 66th could not operate freely with an American infantry company situated at that location. The 66th had to dislodge Delta or run the risk of losing its strategic advantage in the area.

Let the Fight Begin The mortars hit first. It was about 0730 the next morning when the cry, “In-coming!” rent the air. Grunts (as American soldiers were called) dove for cover as the rounds landed in quick succession. Several rounds exploded in trees, sending shrapnel flying everywhere. These chunks made a whizzing sound in the air. ILT Castillon, the FO, was quick to respond with artillery to the suspected location of the enemy tube. You could hear the bark and rumble of 105s and 155s in the distance, then the whir and crash of the rounds. The first casualties from the enemy mortar were reporting in, and a medical evacuation (dust off) helicopter was put on alert. But the artillery appeared to have silenced the mortar for the time being. Then the hill came alive with small arms fire at close range. The NVA set off claymore mines captured from Alpha Company. Both sides used the thick brush and trees as cover. There was little open ground for good target and firing opportunities, except on the three ridgelines. Between these ridges, the slopes were steep and the brush so extremely thick that an enemy could approach within yards of friendly positions and not be seen. The NVA were probing, trying to locate machine gun positions, trained as the guns were on the likely avenues of approach the ridges afforded. Increasing sniper fire soon made it difficult to move around inside the perimeter. One of the 4th Platoon’s M60’s went toe-to-toe with an enemy machine gun. Both were zeroed in. At one point, the gunner, SPC Ralph Marquez, crouched behind his cover and held the M60 over his head, pretty much firing blind. Others helped him zero his direction. When the siege was broken the next afternoon, Marquez found the body of his adversary, along with the gun. In his words, “I nailed the sonovabitch.” At 0815, an hour after the initial action, platoon-size elements of NVA were spotted moving east of the perimeter, while others were seen maneuvering to the west. To keep the NVA off balance, the CO ordered a general “mad minute” to commence, and the troops responded by continuous firing into the unknown. However effective this procedure was in keeping the gooks at bay, it was not the way to conserve ammunition. By 0830 the company was in need of an emergency supply of ammunition, water, and medical supplies. And at the same time, the NVA again opened up its 60mm mortar, and Delta began taking more in-coming rocket fire. These rounds appeared to harm the 3rd platoon the most, since they had the least overhead cover. Thus far Delta casualties were three KIAs and 20 WIAs. But the perimeter remained intact. The NVA had yet to make a serious run for our position. That would come later. At 1130 a helicopter attempted a dust off of seriously wounded. Hovering above the hill, and well aware of the risks, the crew used a cable penetrator to extract several of the seriously wounded. It wasn’t long before the chopper attracted heavy ground fire and started to take hits. Troops from Delta responded with their own suppressing fire as the helicopter hovered. On its way out, the chopper took hits in the tank and limped smoking but safely to an emergency landing in friendly territory. The Rockets Red Glare In the afternoon, the NVA resumed its pressure on the beleaguered company by stepping up the mortar attack and sniper fire. Then came the B-40 rockets, or RPGs (rocket-propelled grenades). These could be employed against infantry with devastating effect by being aimed at trees. When hit, the shattered tree fragments could then become lethal projectiles. One such rocket slammed against a tree in Bauer’s 4th platoon, directly above a three-man foxhole. For some reason, however, it did not explode in the usual manner. When it hit the tree, the explosive material sent the shell casing flying, causing severe injuries to nearby troops, including Rick Schlafer, who was knocked unconscious, suffering a skull fracture and severe facial injuries from the searing shrapnel. But the tree still stood and the shaft was still visible. A true blast of a rocket would have rent the tree and produced far more casualties. In the middle of the afternoon, as ammunition was getting dangerously low, a re-supply helicopter made a mad run for the hill flying at tree-top level, dropping water and other supplies along with ammo. The chopper guys were understandably in a hurry to jettison their cargo, but in their haste, they missed their mark, landing the 4th platoon area. Some of the heavy metal water canisters just missed hitting some of the soldiers, while the rest of the re-supply rolled down the steep slope in front of the 4th platoon and into enemy territory. The slope itself was thick with brush, but the decision was made to go for the goods, hoping that the NVA were thin or non-existent at that particular site. As Bauer recollects, “I told my platoon sergeant to gather hand grenades, that I had a plan. When the grenades were ready, I dove through a sniper zone and rolled up against a tree several yards outside the perimeter. Sensing I was in a safe spot, I then had the sergeant toss me the hand grenades one at a time. One after another, I pulled the pins, and threw three or four on each side of the tree in random distances into the thickets. After the last ‘crump’ of the exploding grenades, a squad was able to make its way to the supplies without incident.” But soon came the tear gas. The NVA were throwing Alpha’s tear gas into the perimeter. The air was thick with smoke and gas. An attack was launched on the third and first platoon side but was repulsed. Smoke and confusion enshrouded the hill. The hill reeked of gas, of sulfur from exploding shells, of sweat from grimy troops, and of the unmistakable whiff from the mounting toll of the dead. CPT Daugherty recalled the incident of what he believed to be the first do die on the hill: “I knew the guy. I had stopped by earlier in the night before checking on troops and we made some small talk. He was glad I came around. Later, when we were taking incoming, he showed up in the CP bleeding badly from the neck. You could see this huge hole. He said a few words and just bled out. Collapsed and died. There was nothing we could do.” Meantime, the artillery continued to pound expected enemy assault routes. Castillon had calculated the likely staging areas of an NVA attack, and sent the 155s pounding forth. We would learn later during the enemy body count how effective this tactic proved to be. It was certainly a crucial factor in the company survival. If the NVA could not mass safely, they could not rush in an organized fashion. On the downside, to avoid the artillery barrage, the NVA were forced to hunker close in to the perimeter where they could cause a heavy dose of small arms damage with the help of captured Alpha Company ordnance. As 3rd platoon troop PFC Byron Adams recalls, “The gooks were right on top of us when the shit really hit. I lost a couple of good buddies very quickly. Steve and Wayne were near me but not the same hole. Steve was in my platoon and I think Wayne was 2nd. When the claymores were being used from Alpha, Steve took almost a direct and there was the briefest of a yell of pain and he was dead. Wayne was up at that point and suddenly he was gone, too. I knew these men well and we were in close proximity of each other. Stuart Halle crawled out to Wayne's body and covered the upper portion with a poncho. I’ll never forget when they went down. But I pretty much lost my memory of events after that. I just sort of blocked it all out.” A Night With Spooky By late evening of 5 March, all was quiet on 947. We were not looking forward to what darkness would bring. At night, the enemy had the advantage. and we knew they would make another run at us. We could only stay alert and use our support resources. One such resource was an air support gunship known as “Spooky.” It was a slow moving, wide-bodied, propeller-driven craft with an enormous machine-gun capability. It sported both the standard 30 caliber and the bigger 50 caliber guns, the latter of which could slash effectively through the undergrowth. Huge flares were dropped to light up the area. As the plane slowly circled the perimeter, both guns fired continuously at unspecified targets near as possible to our positions. Spooky arrived early a.m. on 6 March. It was a rain of death for unprotected NVA. But Spooky was unlucky for a wounded soldier in the command post. His death was not caused by an errant machine gun round fired by Spooky. Instead, he was killed by a flare that failed to ignite. Lying on the ground near the CP was a soldier who had been badly injured the preceding day. As it descended, the flare swung side to side suspended by its parachute and buoyed by the breeze. Those who watched it come down knew it would hit forcefully and wanted to be out of its way. Normally, the burning of the flash powder would lesson the weight so that the remaining carcass was not a concern. But with a full canister of unspent powder, the flare careened down speedily and plunged into the soldier’s head. He didn’t stand a chance. The NVA rushed at first light. They hit in the first and third platoon areas, again softening our positions with another mortar barrage. As they broke through the perimeter, LT Castillon and CPT Daugherty made the supreme decision. They called artillery on our own position. It had to be done. Previously, they had walked it in as close as possible. But now it was time to play the ace. There was no end to its devastating effect. The NVA were stopped dead in their tracks. Their scant cover was no match for the 155s that slammed through the forest canopy. Delta did not lose a man to the friendly fire, another huge lucky break. At first light, Delta regrouped for another onslaught. With a respite from action, the CO decided it was time to push out our tight perimeter in order to give us some breathing room. The 4th Platoon was to suffer from this decision. Daugherty called the platoon leaders to the command post and gave the order. At the appointed time, all platoons were to advance. When the time came, men of the 4th men left their positions at a low crawl and inched forward. Into what was a known sniper space mentioned earlier in the grenade episode, 4th Platoon Sergeant Bruce Thompson crawled, followed by RTO (radioman) Billy Perry, and LT Bauer. The three had proceeded only several meters from their previous “safe” location when a sniper opened fire from the trees to their left. It was the unmistakable high pitch sound of an AK47. The three were the proverbial sitting ducks. There were two short bursts. The first missed to the right. The second was right on target. In succession the platoon sergeant was hit and then RTO Perry. Bauer could see the rounds hitting the first two men and coming toward him. One round landed close enough to kick dirt into his eyes. Then the burst ended. Others in the platoon had spotted the sniper and blew him away. When the sniper was silenced to the great joy of all, Thompson and Perry were pulled back into safe ground. Both survived. The RTO suffered a leg injury, while the sergeant was shot in the buttocks. He agreed to a shot of morphine and was told he wouldn’t be sitting down any time soon. As it turned out, 2nd Platoon had not pushed out its side of the perimeter. This had the effect of leaving the 4th without cover on its flank. The Death of Sgt. Jerry Johnson One of the most popular men of Bauer’s 4th Platoon was SGT Jerry Johnson, mentioned earlier as having been the point man a day earlier during the first encounter with the 66th. He was a superior soldier and liked throughout the company. As LT Bauer recalled the event, “It was also on the morning of 6 March that the saddest event of my life took place. Moving from position to position, I was busy checking on the troops. I went to the farthest right of my strung-out platoon and asked the whereabouts of Johnson. Several of the men in foxholes did not utter a word. They just pointed. I moved forward to a foxhole a good several meters out in front the main line. It served as an observation post and had the best view of an enemy approach. When I got there I saw Johnson, dead, being cradled by his best buddy, machine gunner Ralph Marquez. Johnson had a single bullet hole in his neck or head, as I remember. That scene touches me deeply to this day. I knew Johnson very well and was given to great sadness. But I knew I was not free to show it. Other men were watching closely and as the platoon leader I had to act. I said, ‘All right, c’mon. Let’s get him out of here.’ I grabbed Johnson’s legs and together with Marquez at his arms, lifted him out. We carried him to a corner by the bomb crater, laid him with the other dead, and put a poncho over him. “The dead were stacked a little like cordwood,” Bauer went on. “The crater itself shielded many of the nearby wounded from small arms and mortar fire. Years later, when I saw the movie Platoon, the last scene when Charlie Sheen lifts off in the chopper and looks down was almost identical the real crater on Hill 947. It had a chilling effect.” The CO Makes a Tough Call Late that morning of 6 March, the cry of “in-coming” once more split the air. This would prove to be the end of the mortar, however. A light observation helicopter was overhead at the time and spotted the tube. It called for a gunship, which moved quickly in for the kill. That was the last we heard from the 66th’s attempt to dislodge us from the hill. Gunships, artillery, and the tenacity of our troops carried the day. The NVA mission was either to dislodge us and send us packing, like Alpha Company, or to overrun us. They did neither. On one, occasion, however, Delta was almost delivered over to them. Inexplicably, the brigade commander at one point had ordered Delta to withdraw off the hill, dead, wounded and all. He was flying overhead, observing the action, and gave the order. CPT Daugherty knew that this was a really bad idea, since he did not have the manpower to cover such a retreat with the dead and wounded. The company would be forced into the open where it would be cut to pieces. Daugherty refused the direct order to abandon the hill. Daugherty knew at the time it was not a good career move to refuse a direct order, but he had no choice. His company was at stake. But another strange turn of events took place to save both his career and his company. A second chopper was in the air over the hill and was monitoring the radio exchange between the company and brigade commanders. The person in this chopper was the Army’s overall commander in Vietnam, Gen. Creighton Abrams. Abrams broke into the conversation on his command radio frequency and ordered the brigade commander to break contact and return to base. The brigade commander would be relieved of his command. Turning the Tide By noon on 6 March, the nightmare for Delta was coming to a close. Almost. The company had prevailed against the 66th, which had broken contact. Sensing victory, Delt cautiously left its positions and moved out to explore the area and to do an enemy body count. Within two hours the count of enemy dead were close to 90. Many were clustered together, obviously in staging areas that were targeted by the artillery. In effect, the Americans were able to deliver their coup de grace before they could deliver theirs. A generous pile of captured weapons grew quickly as the men scoured the terrain. Among the enemy weapons were those belonging to Alpha soldiers, a grim reminder of the fate Delta troops were spared. It was definitely a period of some hard earned “down time.” Some weary soldiers had already started a fire to make some hot chow for a grateful change. The Costly Accident There was an urgency to remove the tall trees and develop a viable landing zone for larger helicopters to re-supply the company and to transport the dead and wounded to the rear. Engineers had arrived and were busy at work wiring trees with demolition charges to blow enough room on the hill. Also slated for demolition were two dud mortar rounds impacted closely together in the 4th Platoon area. A soldier stood watch over them so that nobody would step on them and set them off. The duds were wired with the same detonation cord connected to the explosives tied to the trees, so that when the engineers were ready to blow the hill, the duds would be exploded. It was like a string of Christmas tree lights. When the time was right, the engineers would cry the usual “Fire in the hole!” to clear everybody off the hill and out of danger. But the cry never came. No one knows how it happened, but the dud mortar rounds and the trees and anything else wired into them went off, suddenly and unplanned, in a huge blast. Among the serious casualties were two platoon leaders, Bauer and 1LT Willy Wingfield of the 1st. Both had to be medevacked. Bauer had been only a few yards from the duds went they exploded and faced evacuation from Vietnam and two months of hospitalization. Wingfield’s arm was shredded by tree debris. Also, one of the engineers working on the detonation detail was blasted so far from the hill that his body wasn’t recovered until three days later when someone followed the trail of stench from his decaying corpse. The soldier guarding the duds was miraculously unhurt after being lofted high into the air and tumbling to the ground. The Aftermath of Battle Only about 40 able-bodied men of Delta were left to regroup and to welcome thelink-up with sister companies Bravo and Charlie. For some reason, Delta survivors would get no respite from the combat field. Operation Wayne Grey would not end for another month, and they would remain a part of it. In the end, it would be declared a major victory against the Tiger Regiment, the vaunted NVA 66th. Americans would eventually get to Alpha Company’s old location, where up to 15 bodies still lay from the scene of their brief, furious battle. The keys to Delta’s survival were manifold. There was the fortune to surprise the NVA squad escorting PFC Guffy out of the area. This had the effect of sparing Delta from stumbling into an Alpha-like situation. There was the tight defensive perimeter that permitted the strongest fighting stance for the tenacious troops. Then there was CPT Daugherty’s decision to disobey a direct order to abandon the hill and not get shredded in a hasty withdrawal. The chopper re-supply units and the gunship support during the long night were a huge help. Finally, and arguably the most important factor in Delta’s survival, was the constant artillery support called into play by LT Castillon. The 66th NVA could neither get into an effective attacking posture nor, ultimately, to get out from under its rain of terror. 0

6 March 1969. Hill 947 after the battle, moments before accidental explosion of mortar rounds. Note detonation cord on tree in middle to the right of water canister. (Photo by John Bauer) |